The history of St Cyprian's Clarence Gate

Charles Gutch was the fourth son of the Rector of Seagrave in Leicestershire. He was educated at Christ's Hospital and King's College, London, and thereafter at St John's, Cambridge and Sidney Sussex College where he became Prizeman in Classics and Divinity in 1842. He was elected Senior Fellow of his College in 1844 and remained so until he died fifty-two years later. After his ordination, he served in two curacies in his home county of Leicestershire. In 1849 Fr. Gutch took charge, at the request of Dr. Pusey, of S. Saviour's, Leeds. He refused the offer of the living and after a brief period in Bath, he moved to London and by 1864 had served curacies at S. Matthias', Stoke Newington, S. Paul's, Knightsbridge and All Saints, Margaret Street.

He was anxious to acquire a church of his own in London which he could manage on his own lines. It was a time when many large London parishes were being divided in order to facilitate more workable parochial conditions. Fr. Gutch approached the Revd. I. L. Davies, the Rector of Christ Church Cosway Street in St. Marylebone, with a view to building a church in that part of the parish which bordered the neighbouring parishes of S. Marylebone and S. Paul, Rossmore Road. The Rector reacted very favourably to the plan which would relieve him of the responsibility for three thousand souls, about a tenth of his whole cure, and suggested that portions of S. Paul's and St. Marylebone parishes should be handed over to Fr. Gutch also. Neither the Rector of S. Marylebone nor the Vicar of S. Paul's approved of Fr. Gutch’s churchmanship, and so that part of the plan foundered.

He was anxious to acquire a church of his own in London which he could manage on his own lines. It was a time when many large London parishes were being divided in order to facilitate more workable parochial conditions. Fr. Gutch approached the Revd. I. L. Davies, the Rector of Christ Church Cosway Street in St. Marylebone, with a view to building a church in that part of the parish which bordered the neighbouring parishes of S. Marylebone and S. Paul, Rossmore Road. The Rector reacted very favourably to the plan which would relieve him of the responsibility for three thousand souls, about a tenth of his whole cure, and suggested that portions of S. Paul's and St. Marylebone parishes should be handed over to Fr. Gutch also. Neither the Rector of S. Marylebone nor the Vicar of S. Paul's approved of Fr. Gutch’s churchmanship, and so that part of the plan foundered.

The faithful who attended Christ Church were, for the most part, quite comfortably off, but the north-eastern part of the parish, which seemed to have so special an appeal for him, was described as "a neglected and heathen part of London". The 3,000 people in the proposed new district were mostly poor, for whom there was no church or school accommodation. A Mission Church was needed, but land was scarce and the wealthy landowner unwilling to assist. Eventually, two houses backing on to each other and joined by a coal shed in what are now Glentworth Street and Baker Street were rented for use as a temporary chapel. Once the leases were obtained the conversion was entrusted to George Edmund Street, the architect of the Law Courts and a personal friend of Fr. Gutch.

His proposed dedication of the Mission to S. Cyprian of Carthage caused further difficulties. He explained his choice by saying “I was especially struck by his tender loving care for his people, the considerateness with which he treated them, explaining to them why he did this or that, leading them on, not driving them. And I said, 'If only I can copy him, and in my poor way do as he did, I too may be able to keep my little flock in the right path, the road which leads to God and Heaven'." Only a few weeks before the Mission was due to be opened, the Bishop of London protested on the ground that such a dedication would be out of keeping with the rules laid down by himself and his pre¬decessors. He would prefer the district to be named after one of the Apostles. After Fr. Gutch had pointed out to the Bishop Tait that a number of churches bear¬ing the names of saints other than Apostles had been dedicated in the Diocese recently, and that the Appeal had been printed and circulated, Fr. Gutch won the day.

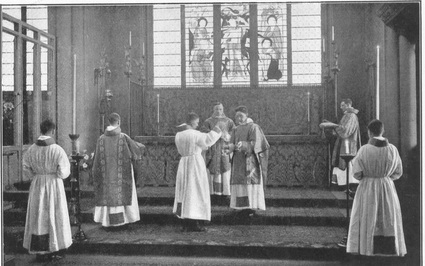

cOn Maundy Thursday, 29 March, 1866, the first Eucharist was celebrated and the following week a Sisterhood was opened next door to the church, whose members were to devote their lives to work in the parish. Six weeks later the scheme of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners constituting the District was approved by the Queen, from which time S. Cyprian's was a distinct Parochial Charge, administered by Fr. Gutch and two assistant clergy.

His proposed dedication of the Mission to S. Cyprian of Carthage caused further difficulties. He explained his choice by saying “I was especially struck by his tender loving care for his people, the considerateness with which he treated them, explaining to them why he did this or that, leading them on, not driving them. And I said, 'If only I can copy him, and in my poor way do as he did, I too may be able to keep my little flock in the right path, the road which leads to God and Heaven'." Only a few weeks before the Mission was due to be opened, the Bishop of London protested on the ground that such a dedication would be out of keeping with the rules laid down by himself and his pre¬decessors. He would prefer the district to be named after one of the Apostles. After Fr. Gutch had pointed out to the Bishop Tait that a number of churches bear¬ing the names of saints other than Apostles had been dedicated in the Diocese recently, and that the Appeal had been printed and circulated, Fr. Gutch won the day.

cOn Maundy Thursday, 29 March, 1866, the first Eucharist was celebrated and the following week a Sisterhood was opened next door to the church, whose members were to devote their lives to work in the parish. Six weeks later the scheme of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners constituting the District was approved by the Queen, from which time S. Cyprian's was a distinct Parochial Charge, administered by Fr. Gutch and two assistant clergy.

For the next thirty years the work of St Cyprian's Mission flourished and expanded, but the little Mission church sat only one hundred and eighty people and was soon overcrowded. Extra services had to be put on to accommodate the numbers and the greatest grief of his ministry was the persistent refusal of Lord Portman to make available a site for the building of a larger permanent church. The main reason for Lord Portman's obstructionist tactics was his dislike for the churchmanship of Fr. Gutch. Unwilling to expose his motives, he decreed that the patronage of the new Church must vest in the Crown, even though an Order in Council had vested it in the Bishop. One of the Trustees stigmatised Lord Portman’s attitude as “weak, frivolous, vexatious and unreal, and justifies the censure expressed in the ‘Times', a few days back, on the 'Criminal Levity of the Peers in Church matters'."

When Fr. Gutch died in 1896, his vision of a permanent Church still unrealized, the Bishop of London, Dr. Mandell Creighton, appointed the Revd. George Forbes, Vicar of S. Paul, Truro, as his successor. The Bishop stressed the urgent necessity for a permanent church, negotiations were opened with the Portman Office for the acquisition of a site and a Building Fund Committee was set up. Finally, Lord Portman agreed to sell a site in the year 1901 for £1,000, a sum much below the market value, provided that, upon the signing of the contract, sufficient money for purchasing the land and building the church should be in the hands of the Bankers, and that the church should be built and ready for consecration by the 1st June, 1904.

When Fr. Gutch died in 1896, his vision of a permanent Church still unrealized, the Bishop of London, Dr. Mandell Creighton, appointed the Revd. George Forbes, Vicar of S. Paul, Truro, as his successor. The Bishop stressed the urgent necessity for a permanent church, negotiations were opened with the Portman Office for the acquisition of a site and a Building Fund Committee was set up. Finally, Lord Portman agreed to sell a site in the year 1901 for £1,000, a sum much below the market value, provided that, upon the signing of the contract, sufficient money for purchasing the land and building the church should be in the hands of the Bankers, and that the church should be built and ready for consecration by the 1st June, 1904.

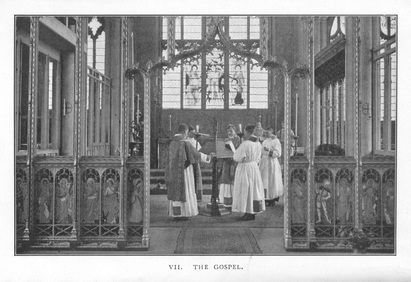

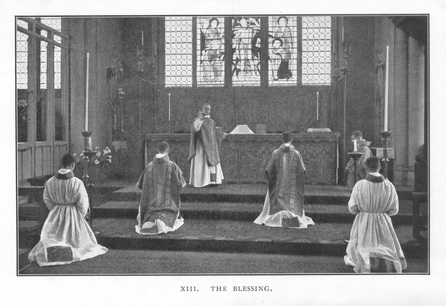

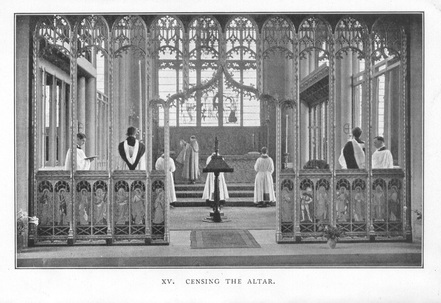

The contract for building was put in the hands of Messrs. Bucknall and Comper, the latter partner being the architect. The Bishop of Kensington blessed the Corner Stone, which was laid by Lady Wilfreda Biddulph, on 7th July, 1902, and almost a year before Lord Portman's term for the contract was due to expire, the church of S. Cyprian was dedicated to the Glory of God and the memory of Charles Gutch by the new Bishop of London. It was the first Church he dedicated in his over-long episcopate. At the Service on 30th June, 1903, Dr. Winnington-Ingram wore a magnificent cope of Russian cloth of gold, which had been worn at the King’s coronation, and a richly jewelled mitre. The ceremony was adapted from the Pontifical of Egbert, the first Archbishop of York who held the See from about AD 736 to 766. It was described at the time as “the real, true ceremonial of the Church of England”, which suggests special pleading. To add to the romantic idealism of the building and the form of service, the floor was strewn in mediaeval fashion with scented flowers and rushes. In the nave were pine, box and rose petals, and on the chancel steps were laid crimson roses and white lilies.

At that time, the Church presented to the eye little more than four walls and stately pillars, although the altars were fully furnished. The task of completing the interior decoration was to be left to succeeding generations.

At that time, the Church presented to the eye little more than four walls and stately pillars, although the altars were fully furnished. The task of completing the interior decoration was to be left to succeeding generations.